| ANCIENT |

|

|

In the Late Iron Age (4th century BC), the Celts began settling the area and upsetting the equilibrium among the previously established centers of population.

After the defeat of the Gauls in the 2nd century BC, the Romans surveyed the land (centuriatio), divided it into plots or jugera (1 jugerum = ca.

Under the brief Byzantine interregnum (553-568),

|

MEDIEVAL |

|

|

Under the Carolingians,

Bishop Cadalo (1048-1077), elected the Anti-Pope as Honorius II, transferred his residence after the 1037 uprising: the new Episcopal seat was a virtual castle, rectangular in plan, it featured fortifications, towers, moat and, inside, a xenodochium or guest-house, chapel and prison.

In

The city walls were enlarged in 1169 to incorporate the new suburbs, their monasteries of San Giovanni (980), San Paolo (985) and San Sepolcro and the Platea Ecclesia Maioris, actually Piazza Duomo.

The square took its present-day aspect with the erection of the Baptistery (ca.1196-1270).

The Piazza del Comune took on its present-day dimensions between 1221 and 1285 with the completion of the Palazzo del Torello (named for Torello da Strada, first podestà or chief magistrate). Thereafter, the Palazzo del Podestà and the Palazzo del Capitano del Popolo went up on the south side, and the Palazzo dei Mercanti, later Palazzo del Governatore, on the north.

The devasting flood of 1117 narrowed the river's bed near the Roman bridge, thereby changing the face of the town's plan. It created, that is, a new public area that was called the «Glara» (Ghiaia), meaning the gravel of its natural paving, first used as the site of public executions. From about 1308, the square is used mostly as a livestock market, a function it will retain up to the 19th century.

In 1210 began the city development's on the Oltretorrente side of the river, where Rubra is located, the «cross-river» area. The progressive extension of these suburban districts made it necessary to enlarge the town's walls first in 1230 and again in 1261, where they remained unchanged till the early 20th century.

| PARMA AND THE SIGNORIA |  |

|

The waning of the Commune in the late 13th and early decades of the 14th centuries led to the subsequent rise of the Signoria.

In the surrounding countryside, the noble Rossi, Sanvitale, da Correggio and Pallavicino families had long estblished territorial dominion by rule of a lord or Signoria - a system that had always been independet of the cty's government and its institutions.

With the changing of the guard from Commune to Signoria,

The new government's policy of centralisation was immediately directed towards refeudalisation, but the local aristocracy, however, proved recalcitrant, unwilling to done the feudal yoke of submission.

The historical records of the period reveal a predominant defensive attitude by the govenment the city walls. Were reinforced, over and over again by Luchino Visconti, who even strengthened the piazza or square until it became a veritable fortress called Keep-the-peace, later demolished under the Farnese.

The Signorias in the surrounding countryside were finding their castes to be the most effective instruments in power politics. Those of the Rossi family at Torrecchiara, Roccabianca, San Secondo and that of the Terzis at Montechiarugolo date to this period. They were manors, stylish and exclusive courts destined to become the collective home of Humanism at

From 1499 to the beginning of Farnese rule in 1545,

| THE FARNESE FAMILY |  |

|

The Duchy of Parma and

This aroused the hostility of the neighbouring Este and Gonzaga families, of the imperial power itself and, chiefly, of the local nobility that led to the assasination of Pier Luigi at

Ottavio Farnese (1547-1586) succedeed Pier Luigi. He showed no such hesitation in ordering the erection of a temporary court. Designed by the architect Vignola, it was begun in 1561 at Co' di Ponte, a wooded, undeveloped site once occupied by the

Ottavio and the other Farnese dukes after him, continued to develop the so-called «Oltretorrente» or «cross-river» land. Important structures such as the churches of Santissima Annunziata (Annunciation) and Santa Maria del Quartiere were built there, respectively in 1566 and 1604.

Ottavio was succedeed by Alessandro (1586-92). As Philip II's general and governor of the

Alessandro's son Ranuccio (1592-1622) completed the Farnese residences with the construction of a vast building called «Palazzo della Pilotta». This massive structure has become the symbol of ducal «absolutism» for the way in which, then as now, it violates the city's plan.

In 1612, Ranuccio's autocratic centralization of power led to a bloody repression of the local nobility. As the death sentence was passed against Barbara Sanseverino, one of the aristocracy's most prominent exponents, her family's estate at Colorno passed into the hands of the duke. The original fortress was transformed into the duke's amenable summer residence.

The death of Ranuccio marked the beginning of an inexorable decline: the golden age was over.

The last descendant of the family, Antonio (1723-31), left no sons upon his death, and the duchy was inherited by Charles of Bourbon, son of Elisabetta Farnese and Philip V. In 1723 he arrived in triumph to take possession of his duchy; in 1734 he left in haste to claim his kingdom.

But he did not go empty-handed. The Bourbon court at

|

THE BOURBONS |

|

|

After the peace of

Appointed prime minister in 1759, Guillaume Du Tillot brought the Enlightenment and its principles to bear on resuscitating the finances and promoting inustry and agricolture.

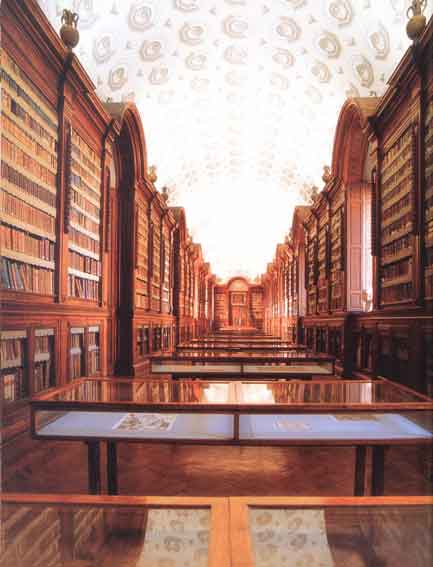

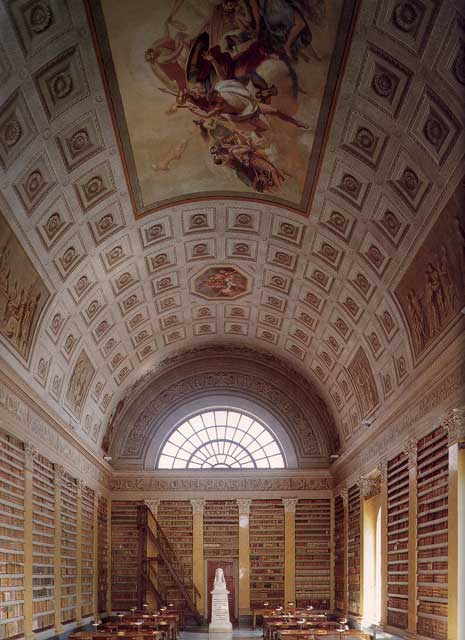

He founded a number of a secular institutions: the Accademia delle Belle Arti (1752) or Academy of Fine Arts, which attracted artists of international renown, including Goya, to its competitions; the Biblioteca Palatina (1762) or Palatine Library; the Stamperia Ducale (1768) or Court Printing Press, set up in recognition of Bodoni; and the Orto Botanico (1768) or Botanical Gardens.

Many of these institutions were, and still are, housed in the Palazzo della Pilotta.

Du Tillot had the Jesuits, who had a virtual monopoly on education in the city, banned from

Though the policy was the prime minister's, the architect who implemented it was Ennemond Alexandre Petitot, summoned to the court from

Under his direction,

The marriage of Ferdinand of Bourbon (1765-1802), Philip's son, and Maria Amalia, daughter of Maria Theresa of

|

MARIE LOUISE |

|

|

The Congress of Vienna (1815) awarded the Duchy of Parma to Marie Louise, daughter of the Emperor of Austria Francis I and Napoleon's wife, although it was stipulated that at her death the kingdom be returned to the Bourbons of Lucca. Beloved by her subjects, and even today celebrated as a legendary figure, she championed a policy of benign public welfare.

Perhaps, her most significant public works initiative was the 1837 «Beccherie» or slaughterhouse project in Piazza Ghiaia. It was the first functionally modern complex of this type, as it housed in a single structure all the city's slaughterhouses.

Her other public works of interest are the Cimitero della Villetta (cemetery) designed by G. Cocconcelli in 1817; the Bridge over the Taro river designed by A. Cocconcelli; in the Palazzo della Pilotta, the Galleria dell'Accademia di Belle Arti or Gallery of the Academy of Fine Arts (the present-day Galleria Nazionale o National Gallery), the Biblioteca Ducale or Ducal Library (today's Sala Maria Luigia or the Marie Louise Wing of the Palatine Library; the Collegio Maria Luigia (1831); the erection of the famous Teatro Regio (1821-28) or Royal Theatre, designed by the N. Bettoli; and the Bettoli-designed facade of the Ducal Palace, thus completing a project begun almost three centuries before. The palazzo was destroyed in World War II.

|

THE RETOURN OF THE BOURBONS |

|

|

After the brief rule of Charles II, who succedeed Marie Louise upon her death in 1847, Charles III became king and literally turned the cityinto an armed camp. He transformed the monasteries of Sts. Paolo and Rocco into barracks and used part of the Palazzo della pilotta to billet troops. The hostility aroused by this policy was such that it culminated in his assasination in 1854.

Louise Mary de Berry, his wife, ruled the duchy as regent of his son. She completely reversed her husband's policy by establishing a prudent neutrality.

Her name is associated with the layng of a new road in the area beyond the river, the Via della Salute (1856-1862). Its houses were planned and erected to newly-formed progressivist building codes designed to salvaguard health standards.

Louise Marie intended the new works to serve as a model for future development of proletarian housing estates. These plans were interrupted when the duchess was forced into exile by the annexation of

|

MODERN |

|

|

At the time of

With the exception of the railway's construction in 1859,

In this period, the Galleria (now Vedi) bridge was reconstructed, the new Bottego and Umberto I (now Italia) bridges were erected, and the Lungoparma was opened by the road between the Umberto I and Caprazucca bridges.

In 1915 was erected the hospital complex.

It was under Fascism, perhaps, that

In the first two post-war decades, the new socio political order combined with the damage caused by the war spurred a boom in the city's construction industry, especially in prime real-estate areas.

BACK TO TOP